This article reviews the ‘companion-volume’ of the facsimile reprint published by Van Wijnen. If interested in the content of the Calov-bible-commentary and Bach’s markings, you’d beter surf to:

- English: https://bach-studies.wursten.be/the-calov-bible-bachs-markings/

- the Annotations: https://bach-studies.wursten.be/bachs-annotations/

- Nederlands: https://bach-studies.wursten.be/nl/calov-uitgeschreven-notities-en-aanvullingen/

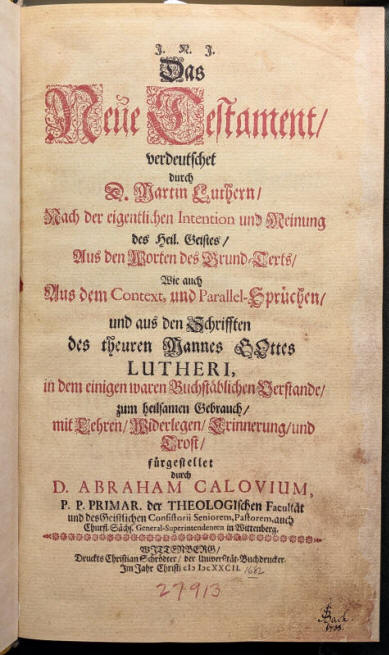

Ever since J.S. Bach’s “Calov Bible” surfaced in Frankenmuth (MI, USA) in 1934, confusion has surrounded this book, both in terms of the physical object and its significance for Bach research. As for the physical object: what is colloquially called the “Calov Bible” or “Bach’s Bible” is, in fact, a biblical commentary, largely excerpted from Luther’s writings and prepared and published in Wittenberg during the years 1681 and 1682 by the seventeenth-century theologian Abraham Calov, who also provided additional exegetical commentary.

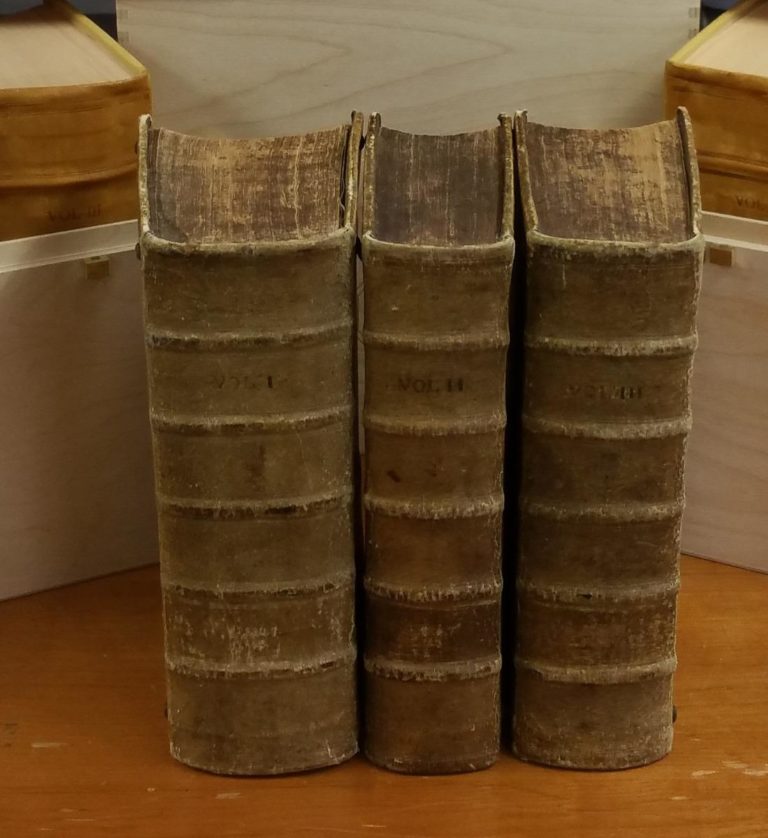

In the copy that Bach owned, the six books of this publication are bound together in three large volumes (in folio) with lavish pigskin bindings and book buttons. Each volume bears Bach’s signature and a date: J.S. Bach, 1733. The confusion surrounding the significance of these books for Bach research stems from the fact that these volumes not only contain Bach’s signature on the title page, but include numerous handwritten markings, such as corrections of typographical errors, a great number of highlighted passages (marginal dashes, sometimes combined with N.B., and text underlinings). There are even five glosses (annotations) in the margin, four of them explicitly dealing with music.

- In 1969, Christoph Trautmann was the first to publish an analysis of the work, together with an inventory of all entries and markings he had discovered. He remained doubtful about the ability to conclusively answer the question of Bach’s authorship, accepting only a very small part of the markings as authentical.

- In 1985, however, Howard Cox published the results of a thorough scientific examination of all the entries and markings, concentrating not on ‘what might be there but on what is there’ (Cox, “The scholarly Detective…”BACH XXV, 1994, p. 31): ink, handwriting, and paper. He inventoried all hand–penned material, and enlisted Hans–Joachim Schulze (who had examined and published Bach’s handwritten documents for the Neue Bach Ausgabe) to assign a rating to each readable handwritten note: certainly Bach, probably Bach, possibly Bach, not Bach. Together with Bruce Kusko (physicist at the Crocker Nuclear Laboratory) he devised a scientific experiment to obtain the chemical fingerprint of the ink types present in the book, using Particle Induced X–Ray Emission (PIXE) analysis. Combining both lines of investigation, Cox and Kusko concluded that nearly all penned entries (notes and markings) could be attributed to Bach with near certainty – a result few had anticipated. Simultaneously, a thorough literary analysis of the readable annotations revealed that nearly all of them — except for the four remarks about church music, and one informative note about a geographical fact — had to be classified as corrections (printing errors, additions of missing text, etc.) rather than as personal notes. A few annotations that contain slightly more information appeared to be more akin to “Lesespuren” than “Lesefrüchte” (terms used by Renate Steiger in her article “J.S. Bach’s Umgang mit seiner Bibliothek,” MuK 1993/2, also in Gnadengegenwart (chapter VI,12), 2002).

With his edition, Cox brought attention to the approximately 400 passages highlighted by Bach, providing a new focus for scholars. To facilitate future research, Cox published a critical edition of Bach’s copy of the Calov Bible Commentary. In it, he assembled the results from the literary and chemical analyses, along with black-and-white facsimile photos of 285 relevant pages from the commentary, including Prof. Ellis Finger’s English translation of the passages marked by Bach: The Calov Bible of J.S. Bach, edited by Howard Cox (Ann Arbor, Michigan 1985). With this, the ambiguity surrounding the significance of the Calov Bible Commentary for Bach research seems to have been clarified. Instead of focusing only on the few well known glosses scholars should turn their attention to the texts that Bach highlighted, mainly marking fragments from Luther’s commentary or Calov’s scholarly exegesis. To investigate these properly, a solid understanding of historical theology (encompassing not just religious doctrine (‘official religion’) but also how people practiced their faith in the early 18th century (‘lived religion’)) would be essential.

Despite this shift in focus, ambiguity about “Bach’s Bible” remained, and no fundamental systematic study of the marked passages has emerged. As far as I can see, this is attributable to three factors:

- The Calov Bible Commentary is a complex work, and difficult to make sense of without historical-theological knowledge.

- Until 2017, Bach’s annotated passages were accessible only through the black-and-white facsimiles in Cox’s publication, which – frankly – did not excel in accessibility. Not because of the quality of the photos as such (they are excellent), but because the book itself is difficult to navigate. The facsimiles and translations come from different parts of the six volumes, and are identified only by the column numbers, without indicating which Bible verse the highlighted commentary pertains to. There is an index, but even so, manoeuvring through it remains challenging.

- The near-simultaneous publication of another book on Bach’s copy of the Calov Bible Commentary, not taking into account the results of Cox’ and Kusko’s research: Robin A. Leaver, Bach and Scripture: The Glosses in the Calov Bible Commentary (St. Louis, Concordia Publishing House 1985). This book unnecessarily perpetuated the confusion about the authorship of Bach of the many markings from the pre-Cox period. This implied, that anyone interested in Bach’s personal copy of Calov’s Bible Commentary between 1985 and 2017 had a choice between two books to get access to it: (1) Cox’s rigorous scholarly work, featuring detailed textual analyses, handwriting comparison reports, chemical analyses, and 286 black–and–white photos, and (2) Leaver’s accessible book with 86 colour photos and insightful but general reflections on the importance of the Bible for Bach. They who entered via Cox’s book, would be convinced that Bach himself had highlighted many passages and would feel confident to use them for their research on Bach’s dealings with the Bible. They who entered via Leaver’s book would have been impressed by the richness of the Bible Commentary Bach held in high esteem, but were left in dubio with regard to the authenticity of the many markings.

These factors, have, in my view, seriously hampered the reception and impact of Cox’s research findings.

In 2017, this situation changed. Publisher Dingeman van Wijnen released a facsimile edition of the Calov Bible commentary. All 4,500 pages are now available in sharp and full-colour reproductions, bound in three hefty volumes. Researchers no longer have to rely on the black-and-white photographs from Cox’s edition. Anyone wishing to consult the marked passages can now simply access and read them, adding as much context to his reading as he wishes (in theory at least, since the facsimile costs €5,500).

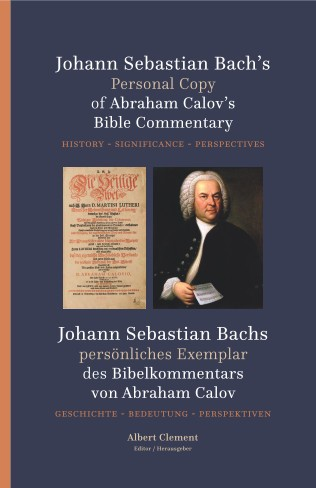

The book under discussion in the present review serves as the ‘companion volume’ to the facsimile edition. This bilingual book (German–English, in parallel columns, with Dutch, English, German and Japanese summaries of the articles at the end) was edited by Prof. Dr. Albert Clement. The subtitle sets high expectations: History – Significance – Perspectives. The book starts with the inventory of all “hand-penned material.” The introduction asserts that this inventory has incorporated all previous lists. Moreover, it claims that errors in previous lists – and in transcriptions – have been corrected. However, this lofty claim was immediately proven to be false when I examined the entries on the first page of the table (p. 45). This is not the place to delve into details, but if one intends to be thorough, a textual correction noted by Cox must not be absent (col. 7: Bach corrects “leuchte” to “feuchte”). Likewise, if an asterisk denotes whether a correction by Bach is also listed in the errata, it must be applied consistently (col. 32 and col. 84: both corrections are in the errata, but in Clement’s table the asterisk is missing). Furthermore, an offset of three unaccountable letters on the reverse of the title page was not recognized by Clement as such (i.e., as a blot), but interpreted as a yet undiscovered entry by Bach: S D G. He classified this as “PN” (Personal Note). However, in 1985, Bruce Kusko analysed the ink of the entry and the offset, both of which differ from all other types of ink used. “In all likelihood, Bach is not responsible for this entry,” Kusko concluded (Cox, 1985, 41; cf. pp. 7–8, [80–81]). Lastly, Clement – following in the footsteps of Leaver – labels an extensive addition to a Luther citation (col. 32, Genesis 3:7) as “PN” (Personal Note), while Bach is correcting a printing error (an omission), which is listed in the errata. A table meant to replace all previous ones but that already fails a preliminary check is of no use. Fortunately, such a table is not really necessary, as nearly all the locations in the six volumes of the Bible Commentary where Bach marked passages have been known since 1985. And the “numerous new discoveries” Clement announces in the Introduction (pp. 22, 25) do not – as far as I could identify them, as he mentions only three – alter the overall picture: they merely add a few more passages to the roughly 400, which one must consult to include all relevant corrections and markings made by Bach.

Does the remainder of this companion volume perhaps redeem the book? Unfortunately, no. The historical articles on Bach’s library and the fate of his copy of the Calov Bible Commentary (by Christoph Wolff and Robin Leaver) provide useful information but contain little that is new. The information about the creation and production of the facsimile is interesting, but not really what I was looking for. I searched for essays that really guide the reader of this book towards the book Bach was reading, helping him navigate it, thus enabling him to read alongside Bach. I only found one: Noelle Heber examines the many markings in the book of Ecclesiastes with the question: How did Bach view rank and class, office and duty, rich and poor? She outlines Luther’s perspective on these issues, which he presented in his 1526 Lectures on Ecclesiastes, printed in 1532, and generously included alongside the biblical text by Calov. Using Bach’s markings, she tracks down those passages that resonated strongly with Bach, and analyses them. It is a solid, enlightening essay, not surprisingly, as it is an extended version of the concluding chapter of her excellent study: J. S. Bach’s Material and Spiritual Treasures: A Theological Perspective (Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press, 2021). Aside, if one consults Leaver’s book (reissued in 2017) the many highlighted passages in Ecclesiastes – used by Heber – are marked as questionable, and thus excluded from the assessment of Bach’s engagement with the Bible.

The other essays sometimes do not even address the Calov Bible Commentary and Bach’s markings, but discuss something else, such as another book (Peter Wollny on Bach’s copy of the Merian Bible, a reprint of a 2012 article; Frits Broeyer on Hutter’s theological compendium), or a piece of music (Jan Smelik on BWV 228). Still other articles are not so much interested in the Calov Bible Commentary and Bach’s dealings with it, but use it to reinforce their own hypotheses about Bach: Heinemann on the ‘Caesura’ of 1733, Greer on the symbolism of red ink in the fair copy of Bach’s Saint Matthew Passion. While the former also demonstrates a serious engagement with texts in the Calov Bible Commentary, highlighted by Bach, the latter uses the Calov Bible Commentary merely to make her hypothesis more plausible. The study of Bach and religion would greatly benefit from a rigorous and well-defined research methodology, including literary criticism.

Fortunately, there is a hidden treasure in this book. There is a very fine article on Calov and his Biblical hermeneutics which is hidden behind a title that suggests an analysis of one of the already well-known annotations about music: Marcel Zwitser, “‘Von Gottes Geist durch David mit angeordnet.’ Bach’s gloss on 1 Chronicles 28 [29]:21 and the Lutheran Doctrine of the Divine Inspiration of Scripture” (pp. 235–273). This essay is useful for understanding how people (in the footsteps of Luther and Calov) could passionately engage with the literal meaning of the Bible in order to achieve a fully spiritual interpretation, without experiencing any contradiction. Zwitser also compellingly demonstrates that understanding a typological reading of the Old Testament is essential for grasping how Luther and Calov (and Bach) read these texts.

In short, after reading this book, I must conclude that the Calov Bible Commentary (the real one in Missouri, or the Van Wijnen facsimile), even with this companion volume, still is in danger of remaining a closed book for the intended and interested reader. An opportunity has been missed to truly undertake the research that Howard Cox envisioned in 1985. However, I do not want to end on a negative note. Bach’s personal copy of the Calov Bible Commentary remains a valuable treasure for Bach researchers. And it has now been digitized. In the interest of Bach scholarship, I would urge the publisher to make the high-resolution photographs of the Calov Bible Commentary available as an e-book (PDF), i.e., alongside the material facsimile that an ordinary person cannot afford to buy. It would also be nice if that e-book then were preceded by a solid historical-theological article on Abraham Calov’s six-volume Bible commentary, which elucidates his veneration for Luther, his passion for a meticulous reading of the biblical text, allowing a modern reader to sense what Bach might have found appealing in the writings of both men. Based on his article in this book, Marcel Zwitser could write this essay. What would be truly helpful is an extensive index, in which all passages highlighted by Bach are linked with both the biblical text and the book/column numbers in the Calov Bible Commentary. Then any benevolent Bach enthusiast could truly open Bach’s personal copy of the Calov Bible Commentary and – at last – start reading alongside Bach.

Dick Wursten

Albert Clement (ed.), Johann Sebastian Bach’s Personal copy of Abraham Calov’s Bible Commentary. History – Significance – Perspectives | Johann Sebastian Bachs persönliches Exemplar des Bibelkommentars von Abraham Calov. Geschichte -Bedeutung – Perspektiven. Van Wijnen, Amersfoort 2023, 416 pp. ISBN 9789051946048. € 99,50